Introduction:

Throughout ancient sanctuaries, a golden artifact commanded profound reverence—the Altar of Incense. This sacred object stood as a powerful bridge between humanity and the divine, with fragrant smoke rising like prayers toward heaven. Today, its spiritual significance continues to resonate across faith traditions and personal spiritual practices, offering timeless wisdom about our connection to the sacred.

Historical Origins and Evolution

Ancient Roots of Sacred Incense Burning

The practice of burning incense dates back to the earliest civilizations. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of incense use in ancient Egypt as early as 3500 BCE, where it played a crucial role in religious ceremonies and funerary rites[1]. The Egyptians believed that incense smoke carried their prayers to the gods and purified sacred spaces[2].

However, the Altar of Incense gained its most detailed description and theological framework within the Hebrew tradition. According to Exodus 30:1-10, God instructed Moses to construct a specific altar for burning incense. This wasn’t a casual addition to religious practices. It represented a purposeful, divinely-ordained medium through which the earthly and heavenly realms could connect.

Evolution Through Religious Traditions

While the altar’s origins are firmly rooted in Hebrew worship, its significance transcended cultural boundaries. Babylonian temples featured elaborate incense altars. Greek and Roman religious practices incorporated similar concepts, with designated spaces for aromatic offerings to their pantheons[3].

Eastern religious traditions developed parallel practices. In Hindu temples, the burning of incense (agarbatti) became a staple of worship (puja), symbolizing the element of fire as a divine messenger. Buddhist monasteries embraced incense as a means of purification and meditation enhancement[4].

The Early Christian Church adopted the altar of incense from Jewish traditions, transforming it into ceremonial censers used during liturgical celebrations. This adaptation reflects how the core concept of the altar—creating a tangible connection between human worship and divine presence—resonated across faith boundaries.

Key Historical Insight

The persistence of incense altars across diverse cultures and millennia demonstrates humanity’s universal desire to create physical bridges to spiritual realms. While forms and rituals varied, the underlying function remained remarkably consistent: facilitating communion between the earthly and the divine.

Significance in the Tabernacle and Temple

Sacred Location and Divine Design

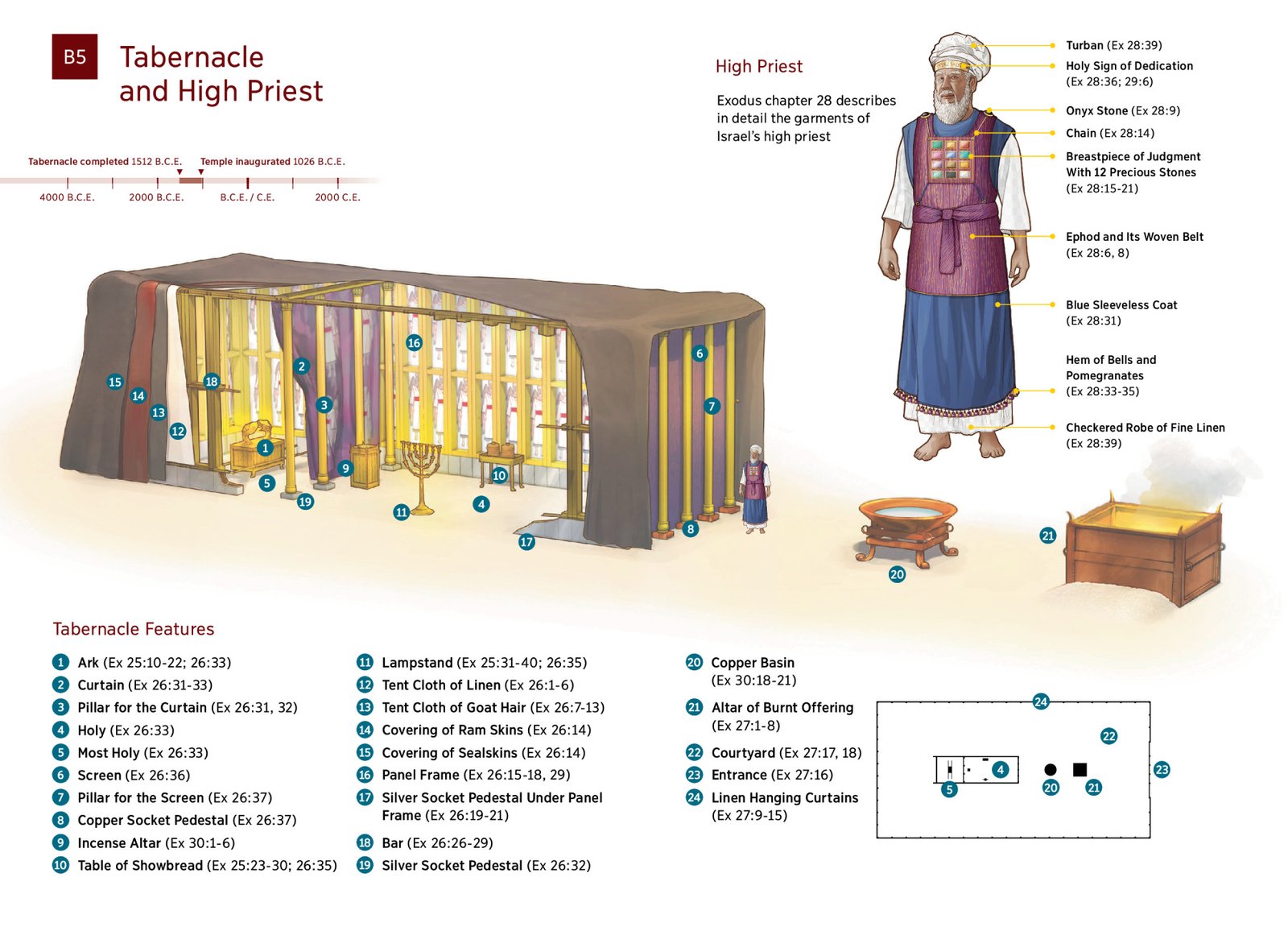

In the Tabernacle—the portable sanctuary described in Exodus—the Altar of Incense occupied a position of extraordinary significance. It stood directly before the veil separating the Holy Place from the Most Holy Place (Holy of Holies) where the Ark of the Covenant resided[5]. This strategic placement wasn’t accidental. The altar’s position represented the threshold between ordinary sacred space and the most intimate divine dwelling.

Constructed of acacia wood and overlaid with pure gold, the altar measured one cubit square and two cubits high (approximately 18″ × 18″ × 36″). It featured four horns at its corners and a golden crown around its top edge. This exquisite craftsmanship reflected the altar’s profound importance in facilitating communication between humanity and God. As Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks notes, “The altar stood at the boundary between heaven and earth, marking the place where the material and spiritual realms meet.”[6]

Ritual Practices and Priestly Duties

The altar demanded precise ritual observance. Aaron, the high priest, was instructed to burn fragrant incense on it every morning and evening when he tended the lamps. This established a rhythm of devotion that punctuated each day with sacred connection. When he approached the altar, Aaron entered a liminal space where human offering and divine presence converged.

On Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), the altar’s significance intensified. The high priest would take a censer full of burning coals from this altar, along with two handfuls of finely ground fragrant incense, and bring them behind the veil. The resulting cloud of incense would cover the mercy seat, creating a protective veil between the high priest and God’s presence[7].

Professor Israel Knohl from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem explains that “the incense offering represents the most intimate form of communication with the divine. Unlike animal sacrifices performed in public view, the incense ritual occurred in relative seclusion, creating an atmosphere of profound intimacy between the priest and God.”[8]

Notable Prohibition

The altar came with strict regulations: no unauthorized incense, no grain offering, no drink offering, and no animal sacrifice could be offered upon it. These limitations emphasized its special purpose as a conduit for prayer and spiritual communion rather than material sacrifice. The altar’s exclusive function underscores that prayer operates in a distinct spiritual category from other offerings.

Symbolism and Theological Meaning

Prayers Rising to Heaven

Perhaps the most enduring symbolism of the Altar of Incense is its representation of prayers ascending to God. This connection becomes explicit in Psalm 141:2, where David writes, “May my prayer be set before you like incense; may the lifting up of my hands be like the evening sacrifice.”[9] This powerful metaphor captures how our spiritual communications rise from the earthly realm to the divine presence.

The visible nature of incense smoke creates a tangible prayer metaphor. As Dr. Margaret Barker, scholar of temple theology, explains: “The rising smoke provided a visible representation of an invisible reality—the trajectory of human prayers entering divine awareness.”[10] This visual element helped worshippers conceptualize how their prayers, though intangible, truly connected with transcendent reality.

Christological Interpretations

Christian theology finds rich Christological significance in the Altar of Incense. The Letter to the Hebrews draws parallels between temple worship and Christ’s redemptive work. Jesus is portrayed as both the ultimate High Priest who enters God’s presence and the perfect mediator who makes our prayers acceptable[11].

Theologian N.T. Wright observes that “in Christ, the gap between heaven and earth that the altar symbolically bridged has been permanently spanned. He doesn’t just carry our prayers to God; he embodies the perfect communion between humanity and divinity.”[12] This understanding transforms the altar from a shadow to a fulfilled reality in Christian thought.

Revelation’s Heavenly Altar

The Book of Revelation provides a striking image that completes the altar’s symbolic trajectory. In Revelation 8:3-4, John describes a golden altar before God’s throne in heaven: “Another angel, who had a golden censer, came and stood at the altar. He was given much incense to offer, with the prayers of all God’s people, on the golden altar in front of the throne. The smoke of the incense, together with the prayers of God’s people, went up before God from the angel’s hand.”[13]

This apocalyptic vision suggests that the earthly altar prefigured an eternal reality. Prayer isn’t just symbolized by incense; in some mysterious way, our prayers actually accompany the heavenly incense before God’s throne. Biblical scholar Craig Keener notes that “John’s vision validates the temple symbolism by revealing its heavenly prototype, showing that the connection between incense and prayer transcends human ritual to reflect cosmic reality.”[14]

Sacred Incense: Composition and Meaning

The Divine Recipe

The incense burned on the altar wasn’t arbitrary in its composition. Exodus 30:34-38 provides a specific divine recipe combining equal parts of four aromatic substances: stacte (likely a form of myrrh or storax), onycha (possibly derived from certain shellfish opercula), galbanum (a resin with a strong odor), and pure frankincense[15]. These ingredients were to be blended with salt into a pure and holy mixture.

Notably, this exact formula was exclusively reserved for sacred use. The text explicitly forbids replicating this blend for personal use, declaring such misappropriation as cutting oneself off from the community. This exclusivity underscores the incense’s role as a sacred medium, not merely a pleasant fragrance.

Symbolic Layers in Each Element

Each component carried symbolic resonance that enriched the incense’s meaning:

- Stacte: Often associated with tears or drops, it symbolized the prayers of petition and sorrow rising to God.

- Onycha: With its marine origins, it represented the breadth of creation participating in divine worship.

- Galbanum: Known for its initially unpleasant but ultimately enriching aroma, it symbolized how difficult experiences are transformed through prayer.

- Frankincense: Representing purity and sanctity, it symbolized the perfect prayer of praise.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch observed that “the four ingredients represent the diversity of human experience—joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain—all of which are legitimately brought before God in prayer.”[16] The complex, layered aroma created by these elements mirrors the multifaceted nature of authentic spiritual communication.

From Ancient Formula to Modern Spiritual Practice

While we may not have access to the exact ancient formula, modern spiritual practitioners often use incense blends that incorporate elements like frankincense and myrrh to create sacred space. These contemporary adaptations honor the ancient understanding that fragrant smoke creates a sensory bridge between material and spiritual realms.

The Altar of Incense in Contemporary Practice

Liturgical Traditions

The altar of incense finds continued expression in formal religious practices today. Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and some Anglican churches use censers during worship services. As these vessels swing, releasing fragrant smoke throughout the sanctuary, they create a sensory connection to ancient practices while symbolizing prayers rising to heaven[17].

Father Thomas Hopko, Orthodox theologian, explains that “incense engages the senses in worship, reminding us that we don’t just think our prayers—we experience them with our whole being. The visible smoke helps worshippers understand that their prayers truly ascend to God’s presence.”[18] This sensory dimension creates a worship experience that transcends purely intellectual engagement.

Interfaith Resonances

The concept of incense as a prayer medium extends beyond Abrahamic traditions. In Buddhist practice, incense creates an atmosphere conducive to meditation and symbolizes moral perfection. Hindu puja rituals incorporate incense as one of the sensory offerings (along with light, food, etc.) that honor divine presence[19].

This cross-cultural resonance suggests something profound about human spirituality. Dr. Diana Eck, professor of comparative religion at Harvard, notes that “the nearly universal human impulse to use fragrant smoke in worship points to our inherent understanding that spirituality involves bridging visible and invisible realities.”[20]

Personal Spiritual Practice

Beyond institutional religion, many individuals have rediscovered the spiritual value of incense in personal practice. Burning incense during prayer, meditation, or contemplative reading creates a sensory environment that facilitates spiritual focus. The ancient symbolism resonates even in contemporary contexts.

Psychologist Dr. Edward Hoffman observes that “sensory cues like incense can help modern people transition from scattered attention to spiritual receptivity. The rising smoke provides a visual focal point that naturally draws attention upward and inward.”[21] This psychological dimension helps explain why the practice remains meaningful across centuries and cultures.

Modern Scientific Insight

Recent neuroscience research suggests that certain incense components activate channels in the brain that alleviate anxiety and depression. A 2008 study published in the FASEB Journal identified how incensole acetate, a Boswellia resin compound, affects brain areas regulating emotions[22]. This finding provides an intriguing scientific perspective on why incense has been valued in spiritual practices—it may literally help create psychological states conducive to contemplation and communion.

Creating Your Personal Altar of Incense

Sacred Space in Contemporary Life

The ancient concept of an altar of incense can be meaningfully translated into modern spiritual practice. Creating a dedicated space for prayer, meditation, or contemplation establishes a physical location that supports your spiritual connection. This doesn’t require elaborate religious affiliation—it can be adapted to various spiritual perspectives while honoring the core principle of creating sacred space.

Spiritual director Mary Earle suggests that “designating a specific location for spiritual practice helps create a psychological boundary between everyday activities and sacred time. The physical space becomes a threshold that helps us transition into a different quality of awareness.”[23]

Practical Elements for a Modern Altar

Consider these elements when creating your personal altar:

- Location: Choose a quiet area where you won’t be frequently disturbed. Even a small shelf or corner can become a dedicated sacred space.

- Incense: Select quality incense with natural ingredients. Resins like frankincense and myrrh connect most directly to ancient practices, but choose fragrances that support your spiritual intentions.

- Holder: Invest in a proper incense holder to ensure safety and respect for the practice.

- Meaningful objects: Include items that carry spiritual significance for you—sacred texts, natural elements, meaningful symbols, or images that evoke transcendence.

Practical Rituals for Spiritual Connection

The power of an incense altar emerges through consistent practice. Consider these approaches:

- Morning and evening prayers: Echo the ancient temple practice by bookending your day with moments of spiritual connection.

- Intentional lighting: When lighting incense, bring conscious awareness to what you’re doing. Some traditions suggest lighting incense with your right hand while supporting your right elbow with your left hand—a posture that encourages mindfulness.

- Verbal expression: Consider verbalizing your intentions, prayers, or gratitude as the incense begins to release its fragrance.

- Contemplative presence: Remain present as the incense burns, allowing its rising smoke to guide your attention upward. This practice combines sensory focus with symbolic meaning.

Spiritual teacher Mirabai Starr notes that “the beauty of creating personal ritual is that it allows us to connect with ancient wisdom while expressing our unique spiritual journey. The key is approaching the practice with authenticity and reverence.”[24]

Health and Safety Considerations

When incorporating incense into spiritual practice, consider these important factors:

- Ensure proper ventilation when burning incense

- Consider respiratory sensitivities—some people may need to use less smoke-producing alternatives

- Never leave burning incense unattended

- Keep incense away from flammable materials

- Consider pets’ sensitivities to smoke and fragrance

Conclusion: The Enduring Sacred Bridge

The Altar of Incense stands as one of humanity’s most enduring spiritual metaphors—a physical manifestation of our desire to connect with realms beyond the visible. From its ancient origins in the Hebrew Tabernacle to its contemporary expressions in churches, temples, and personal spiritual spaces worldwide, this sacred object continues to facilitate communion between earth and heaven.

The altar reminds us that spiritual connection isn’t merely intellectual or emotional—it engages our full sensory experience. Through the rising fragrance of incense, we find a tangible expression of intangible realities. Our prayers, like the smoke, ascend beyond our immediate surroundings, carrying our deepest hopes, gratitude, and devotions to transcendent realms.

Whether encountered in formal liturgical settings or adapted for personal spiritual practice, the altar of incense invites us into ancient wisdom while speaking directly to contemporary spiritual hunger. In a world often characterized by fragmentation and distraction, this sacred tradition offers a centered, sensory pathway to presence and connection.

Perhaps most significantly, the altar of incense teaches us that the boundary between physical and spiritual realms isn’t as impermeable as we might assume. Through intentional practice and symbolic understanding, we can create genuine connections that transcend the visible world while remaining firmly rooted in embodied experience.

“The Altar of Incense reminds us that prayer is not merely words spoken into emptiness, but a real connection established between heaven and earth—a connection made tangible through sacred practice and divine promise.” — Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel[25]

As we recover this ancient wisdom for contemporary spiritual life, we join countless generations who have found in the rising smoke of incense a powerful reminder that our spiritual yearnings truly reach the divine presence. The altar stands as an invitation—to pray, to connect, to transcend, while remaining fully present in our embodied experience of the sacred.

References

- Manniche, L. (1999). Sacred Luxuries: Fragrance, Aromatherapy, and Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press, pp. 27-42.

- Frankfurter, D. (1998). Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance. Princeton University Press, pp. 119-124.

- Elsner, J. (2007). Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text. Princeton University Press, pp. 225-231.

- Reader, I. & Tanabe, G. (1998). Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan. University of Hawaii Press, pp. 32-37.

- Haran, M. (1985). Temples and Temple-Service in Ancient Israel. Eisenbrauns, pp. 158-165.

- Sacks, J. (2009). Covenant & Conversation: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible. Maggid Books, p. 241.

- Milgrom, J. (1991). Leviticus 1-16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible, pp. 1024-1031.

- Knohl, I. (2007). The Sanctuary of Silence: The Priestly Torah and the Holiness School. Eisenbrauns, p. 104.

- Tate, M. E. (1990). Psalms 51-100. Word Biblical Commentary. Word Books, pp. 413-415.

- Barker, M. (2004). Temple Theology: An Introduction. SPCK Publishing, p. 78.

- Koester, C. R. (2001). Hebrews: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible, pp. 382-387.

- Wright, N. T. (2016). The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’s Crucifixion. HarperOne, p. 183.

- Beale, G. K. (1999). The Book of Revelation: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Eerdmans, pp. 454-458.

- Keener, C. S. (2000). Revelation. NIV Application Commentary. Zondervan, pp. 251-252.

- Propp, W. H. (2006). Exodus 19-40: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Bible, pp. 485-490.

- Hirsch, S. R. (1989). The Pentateuch: Translation and Commentary. Judaica Press, p. 568.

- Taft, R. F. (1992). The Byzantine Rite: A Short History. Liturgical Press, pp. 68-72.

- Hopko, T. (1984). The Orthodox Faith: Worship. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, p. 42.

- Flood, G. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press, pp. 208-212.

- Eck, D. L. (1998). Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. Columbia University Press, p. 75.

- Hoffman, E. (2010). The Wisdom of Maimonides: The Life and Writings of the Jewish Sage. Trumpeter, p. 129.

- Moussaieff, A., et al. (2008). “Incensole acetate, an incense component, elicits psychoactivity by activating TRPV3 channels in the brain.” The FASEB Journal, 22(8), 3024-3034.

- Earle, M. C. (2007). The Desert Mothers: Spiritual Practices from the Women of the Wilderness. Morehouse Publishing, p. 54.

- Starr, M. (2013). God of Love: A Guide to the Heart of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Monkfish Book Publishing, p. 187.

- Heschel, A. J. (1955). God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 341.